Functionality and use of design

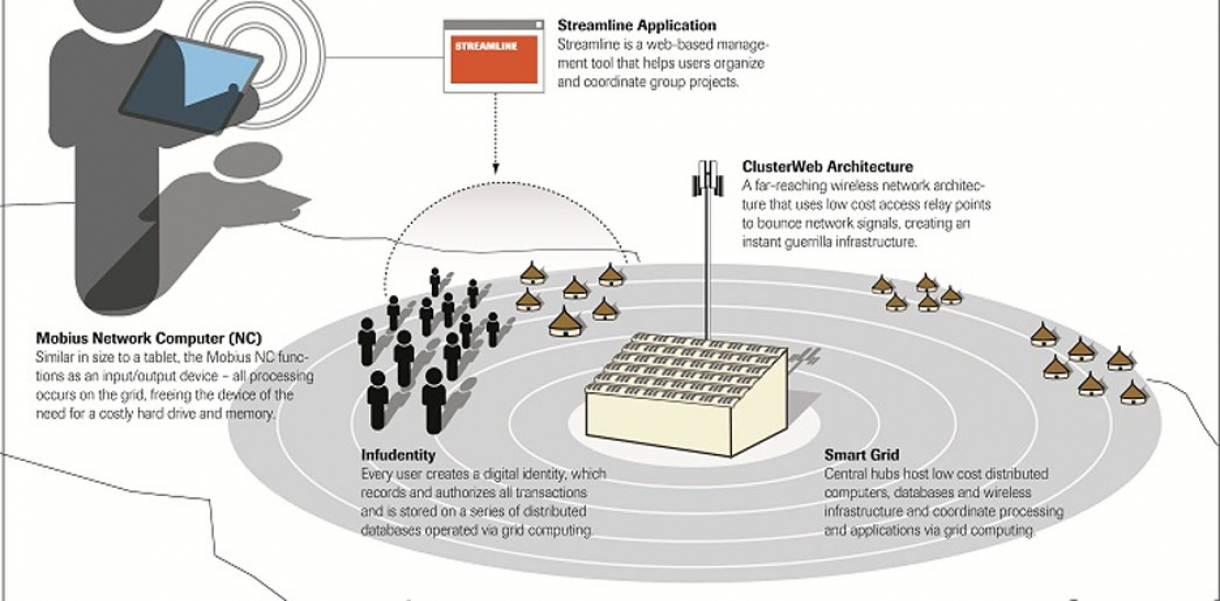

Project Infusion creates infrastructure, tools and services to improve an individual's ability to function in the marketplace. The Infusion network supports simplified input/output devices that access wirelessly networked servers. With all data and software resident on the servers, grid computing supplies low-cost, high-powered computing for business, personal and community activities.

How did this design improve life?

Project Infusion is a template for a transformational business that can change the way of life for the four billion people at the bottom of the economic pyramid. In a seminal paper published in 2002 ("Serving the World's Poor Profitably", Harvard Business Review [September 2002]: 48-57), C. K. Prahalad and Allen Hammond made a strong case that corporations not only can do business with considerable success at the bottom of the economic pyramid, they can be highly instrumental in bootstrapping fledgling economies.

The reluctance of companies of the developed world to invest in the developing world is fueled by deeply ingrained beliefs: "Companies assume that people with such low incomes have little to spend on goods and services and that what they do spend goes to basic needs like food and shelter. They also assume that various barriers to commerce -- corruption, illiteracy, inadequate infrastructure, currency fluctuations, bureaucratic red tape -- make it impossible to do business profitably in these regions." These assumptions are outdated and often just plain wrong. "Take the assumption that the poor have no money. It sounds obvious on the surface, but it's wrong. While individual incomes may below, the aggregate buying power of poor communities is actually quite large." The idea that the poor do not waste money on nonessential goods is also incorrect. "In fact, the poor often do buy 'luxury' items. In the Mumbai shanty town of Dharavi, for example, 85% of households own a television set, 75% own a pressure cooker and a mixer, 56% own a gas stove, and 21% have telephones. That's because buying a house in Mumbai, for most people at the bottom of the pyramid, is not a realistic option. ...They accept that reality, and rather than saving for a rainy day, they spend their income on things they can get now that improve the quality of their lives."

Project Infusion demonstrates how a high-technology company or consortium of companies can make money "infusing" the means for billions of people at the bottom of the pyramid to work more productively and live more proactively.

The Infusion system is a wireless computer network through which all computation, data storage and software services are provided, requiring users only to pay a nominal subscription fee and purchase, lease or rent a low-cost input/output device. The system's infrastructure and applications bring the power of the information age to the bottom of the pyramid by taking advantage of:

Shared Buying Power. While individual incomes may be low, the aggregate buying power of poor communities can be quite high.

Cooperative Business. When individuals unite under shared goals, the strength of the composite group can sustain economic viability for all involved.

Economies of Scale. When services are shared by many, economies of scale reduce the investment required to build necessary infrastructure.

The Infusion system encourages involvement at many levels. Users can engage the system conventionally as a subscriber, but also as a renter of services (in community technology cafes), as a software application builder (using a Linux-based open source architecture), as an IT supporter, as an application educator, as a repair technician or even as a technology recycler. In the last case, engagement is possible because the Infusion system recognizes the problem of e-waste. The system takes a sustainable view. A business can be built around the reuse of technology used in the system. Basic circuit boards, LCD screens, batteries and plastic materials can be recycled and either returned to the system or converted into other useful, saleable products.

The Infusion system supports an entrepreneurial approach to work. By so doing, it makes it possible for individuals and small groups to create a business with very little investment. For example, a fisherman can lease a mobile I/O device individually or with a group of friends and, using a minimum of system applications, can coordinate his catch with demand in the market while out at sea. This can be done at a cost of just cents per day. As the system works to increase the new company's worth, more applications can be applied, extending company capabilities and contributing to its growth. In time, the same fisherman can be coordinating a fleet of vessels supplying many markets.

Providing smart, networked tools to the bottom of the pyramid begins a process of bridge building within and between communities and cultures. Bringing such a massive user base online has obvious financial benefits to the provider (and, thus, a built-in incentive for action), but it will have widespread social and economic effects also. Governments will be able to help entrepreneurs to extend goods and services to regional and global markets, and information and social services normally difficult to provide in remote areas will become deliverable at a level of thoroughness heretofore impossible to achieve.

Drawbacks of life improvement

To successfully implement Project Infusion, any multinational company must recognize potential obstacles and drawbacks and take action early to circumvent them.

Scale

The first problem is the sheer scale of implementation. For a network of this scope to become truly effective, it must capture a significant portion of the population in its target region. This is challenging given the populous, low-income regions that comprise the bottom of the economic pyramid. From a market perspective, buyers will not adopt the system if it does not also serve sellers. From a technology perspective, users in a rural area cannot adopt the system if there are not others in the same area using it. Finally, from a business perspective, a multinational will only see a return on this high-cost investment if sales are high, as margins will necessarily be low.

Comment. To mitigate the risks associated with scale, the project can apply a phased approach to introduction. Test markets can be identified, and products introduced first with opinion leaders influential locally. After a market proves to be worthy of further investment, sales centers called Community Access Outlets (see description in the presentation at http://id.iit.edu/profile/gallery/infusion/) can then be constructed and, local citizens can begin Skill Builder Foundation Training (see presentation). In this way, the company can begin to understand a region's potential without over-investing, and can add hubs incrementally as the network grows.

Localization

A second drawback involves the fact that within a potential market of four billion people, many distinctly different cultures must be understood. Project Infusion involves not only designing products for local cultures, but also introducing, training, and marketing, selling and supporting entire systems for these differing environments. An appropriate pricing structure for a town in China, where item costs are set and fixed, may be completely offensive to a street fair vendor in urban India who prides himself on haggling for the best deals. Issues such as this exist on many levels, and any multinational company who explores opportunities at the base of the economic pyramid must take steps to ensure local concerns are considered and generic assumptions are challenged.

Comment. To deal with the localization issue, a company can initiate contact with the target country's government. Through dialogue, it can then seek to understand basic laws and business practices, local competition and public monopolies, and regions in greatest need of economic activity. Since Project Infusion stimulates local, regional and eventually national economies, governmental bodies should be more than willing to invest in this partnership. The next step in understanding local cultures is to become fully immersed in them. Cross-functional teams of cultural anthropologists, ethnographic researchers, design engineers and marketing personnel should spend time in each city or town, talking with local business people, visiting sales spaces and observing businesses. The purpose here is to understand in cultural terms the ways in which people relate to each other, use products and services, and earn an income. The ultimate goal is an understanding of local businesses and the ways in which Project Infusion can help them start up, grow and prosper.

Adoption of Technology

Finally, the proposal of Project Infusion begs the question: will people in extreme poverty actually be able to afford and learn how to use high-tech products like the Network Computer devices (see presentation)? The reality of the bottom of the economic pyramid is that some people cannot afford to eat every day, and have never seen a laptop computer. People may not be willing or able to learn how to use NC devices without education and experience in technology.

Comment. "Inexperienced" does not mean "incapable of learning." If the product is inexpensive enough, and it benefits people's life enough, people will buy it and learn how to use it. Examples abound. Cellphones were adopted quickly, all across India, because they bring an immediate, tangible benefit to a user's life. UT Starcom is a cellphone provider that has used mesh technology to successfully target the dense, urban poor of China. Project Infusion addresses adoption in several ways: through training and skill building, language translation and contextual design, and the power of co-creation.

Research and need

The Infusion system was created using Structured Planning methodology, a process for conducting research and incorporating results in the planning process. For a full description of the process, see papers by Charles L. Owen at http://www.id.iit.edu/ideas/papers_archive.html/.

35% of people in India earned less than $1 a day last year. And this situation is not unique to India. The world's population is mostly poor, with fully 65% -- four billion people -- earning less than $2,000 per year. Project Infusion was inspired by the now famous 2002 article in the Harvard Business Review, "Serving the World's Poor, Profitably." In this article, noted business scholars C.K. Prahalad and Allen Hammond examined this huge population as a very interesting market, widely underestimated and potentially capable of major service to the global economy.

To identify needs, the eight-person planning team began with research about Prahalad's and Hammond's theories. The bottom of the economic pyramid includes the majority of the world's developing nations, and a major task was to identify the extent of problems and opportunities. Many issues needed to be addressed, including how basic needs like health, sanitation, food and water are being met, and how more subtle problems of cultural norms affect the adoption of modern products. The team concluded that a major design opportunity was a vehicle for personal business applications, and that the ripple effect of economic achievement would bring about improvements in many problem areas.

To understand the context for design, the team conducted primary and secondary research on three key topics. First, the team examined cultural, issues in order to learn what was desirable. Meetings with anthropologist Jean Carnavan, who has done ethnographic research in China, Brazil and India, were highly instructive. Photos were collected from the slums of Mumbai and Calcutta. International students at the Institute of Design from India and China were consulted. And the cultural human factors surrounding business practices in third-world countries were studied. The team concluded that while a project of this magnitude would need consistencies of infrastructure in order to achieve economies of scale, applications should leave room for customization wherever possible.

Next, to learn what was viable, the team studied the unique business models of companies targeting the bottom of the economic pyramid. Grameen Telecom, whose village phones are owned by a single entrepreneur, but used by the entire community, demonstrated that, while most individual incomes are low, the aggregate buying power of poor communities can be quite large. Amul, an Indian company that provides dairy products to urban consumers, was another highly instructive study. Every day, milk is collected from remote villages and pasteurized at the Amul plant, where it is packaged and distributed to urban centers around India. The system is providing dependable wages to rural producers, and quality products to urban residents. Under Amul's cooperative business model, when a group of distant individuals unite under a shared goal, the results lead to combined economic sustainability.

The team also studied Aravind Hospital in India, an institution whose actions exemplify the forward-thinking strategy of high-cost investment. Aravind has invested in expensive medical equipment for corrective laser eye surgery. The delivery cost per patient is now so low that eye surgery in the region is cheaper than prescription glasses. Because of its considerable number of satisfied customers, Aravind Hospital has recovered its initial investment at an astonishing rate. From this research, it was concluded that the best solution would integrate multiple strategies: the market model of shared buying power, the cooperative business model, and the investment strategy of planned return on investment.

Finally, the team studied technology in order to learn what was possible. The technological capabilities of large multinationals, such as IBM and Hewlett-Packard, as well as those of smaller niche providers like Techsonic Industries, Inc., maker of the Humminbird Smartcast wireless wrist fish finder, and Univa Corporation, creator of grid computing, were studied. Through these investigations, it was determined that the best solution would be a combination of complex emerging technologies, such as open source development, grid computing and distributed networks, with adaptations of simpler ones of the past, such as interactive computing with I/O devices as user interfaces.

Great problems are borne out of grand, seemingly impossible challenges. Project Infusion is a blueprint for a system fitting Prahalad's and Hammond's vision. It shows how a multinational company or consortium of companies could positively affect billions of people -- and make money.

For a presentation of the project, see http://www.id.iit.edu/profile/gallery/infusion/. An in-depth report is also available at the same URL.

Designed by

Eric Holubow, Lucas Daniel, Rinku Gajera, Stephen Schneider, Sara Cantor, Rachel Hinman, Ah Young Kim & Matt Locsin - United States