Functionality and use of design

The Kinkajou uses a five-watt, white LED and an array of seven plastic lenses to project an image or a page of text from microfilm. Optimized for night-time use in a classroom without electricity, the Kinkajou can project an image up to three meters across onto practically any flat surface.

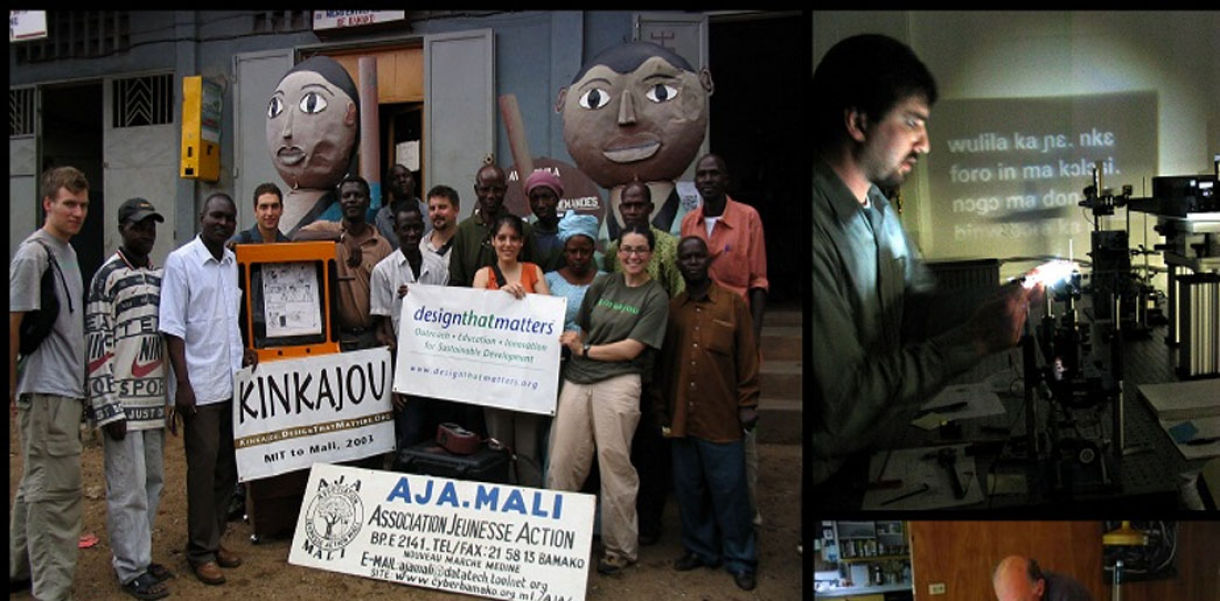

Kinkajou projectors are currently being piloted as a teaching tool in night-time adult literacy classes in 45 sites in rural Mali. Kinkajou projectors are also under evaluation at the Institute pour l'Education Populaire (IEP) in Mali, and the Center for Mass Education in Science in Bangladesh. Vast potential for use worldwide, particularly in rural communities without electricity.

Drawbacks of life improvement

DtM is working to address the issue of local production of content, which is the chief drawback of the current design. Currently, organizations using the Kinkajou are required to send electronic or paper copies of their curriculum to the US or Europe to be converted to microfilm. This is not a problem for World Education, which already produces its content in the United States, but it is not convenient for indigenous organizations like IEP and CMES.

DtM has identified a variety of relatively low-cost, low-volume off-the-shelf microfilm production systems, including Kodak's US$800 "desktop microfilmer" (originally intended for the banking industry). They continue to research and evaluate other options, including other ways of producting microfilm locally, as well as the costs and benefits associate with other media such as 35mm film and slides (which can be developed almost anywhere in the world) and computer-printable overhead transparencies.

DtM is also working on the problem of the off-grid power supply. The current design includes the use of a standard UPS battery, a charge controller, and a 12-watt solar panel. This system, at US$120, is too expensive for most rural communities to afford without subsidy. DtM is currently working on the development of a lower-cost, human-powered battery charging system, with a target of delivering a use-to-charge ratio of 10:1 at a cost of under US$50 in volumes of 5,000-10,000. Methods under development include machines based on sewing machine treadles and a rowing motion adapted from a popular exercise machine.

How did this design improve life?

One in five adults worldwide does not know how to read. In other areas, for example rural regions of West Africa, up to 75% of the adult population is illiterate. According to Barbara Garner of the World Education Organization, it's the lack of resources--specifically access to books and lighting--rather than the lack of interest in education that contributes to these numbers.

Design that Matters (DtM) has partnered with World Education, a Boston-based non-governmental organization with adult literacy programs in 26 countries around the world, to design technology that facilitates education where it is needed most. Take Mali, for example. Books are hard to come by: they must first be shipped from the U.S. to Mali and then transported to all of Mali's 11,000 villages, a process that is both time consuming and expensive. And even if they do arrive, they don't last long, given Mali's extreme,near-desert climate. Thus a large portion of World Education's budget is devoted to providing materials, and even so, many students go without books.

Even with books, adults literacy students face another hurdle: as most students must work during the day, they take classes at night, reading by lanterns and flashlights in villages without electricity. It is therefore difficult, particularly as an adult, to take the time to learn how to read.

The final hurdle is one faced by teachers. Tools favored by educators, such as visual aids designed to be viewed by the whole class at once, can't be modified for use at night. As a resullts, teachers spend time in class with their backs to students writing on the backboard rather than facing and teaching them.

Kinkajou takes the form of a microfilm projector. Combining microfilm technology with light-emitting diodes (LEDs), Design that Matters has found the perfect combination and application for what was once considered an obsolete technology. Solar panels power the system. The LEDs last 10,000 hours. Low-cost plastic optics, adapted from toys, facilitates night-time projection. Microfilm is an extremely durable medium, rated to last up to 100 years, in a range of extreme conditions. And the technology is cheap: 10,000 pages can fit on a single spool of microfilm for $25; copies can be made off the master for $12 a piece--easily accomodating World Education's entire adult curriculum, with room left for an entire reference library. Plus, teachers finally are free to face their students and teach them.

The design is optimized for its intended market of rural communities in developing countries, with simple user cues and a rugged, dust-proof housing, and includes a battery, charge controller and solar panel for off-grid use. The design requires no tools more complicated than pocket change for maintenance.

Currently 45 prototype Kinkajou microfilm projectors are going through pedagogical evaluation in villages across rural Mali, to test their effectiveness as a teaching tool. This test alone will reach over 2,000 adult students. Once the study is complete, Design that Matters will begin wider distribution of the technology to World Education and other non-profit organizations to reach as many as possible of Mali's 11,000 villages, as well as other rural communities around the world.

Ashoka Fellow Dr. Maria Kieta and her Institute for Popular Education (IEP)--a model elementary school considered one of the best in Africa--is experimenting with ways this can be applied in their classrooms. Ashoka Fellow Dr. Muhammad Ibrahim, director of the Center for Mass Education in Science (CMES) in Bangladesh, is exploring the technology for use in CMES's 500 "second-chance education" schools, which teach trades as well as basic math and science to over 30,000 adolescents Bangladeshi school drop-outs each year.

The Kinkajou is also under evaluation as a training tool for rural technicians in the Mali Folkecenter's village renewable energy program--as part of a larger market study to identify additional applications for the Kinkajou Projector in underserved communities worldwide.

Research and need

Throughout the design process, Design that Matters worked closely with client organization World Education to allow them, in effect, to design the solution to their problem of books and lighting. This process included multiple field evaluations in Mali and a variety of formal and informal customer needs evaluations.

As previously mentioned, through Design that Matters' collaborative design process over 180 volunteer students and professional from around the world have contributed to the development of the Kinkajou, including students at MIT, Stanford, Harvard, Cambridge University (UK), Tufts University, Worcester Polytechnic and Babson College, and professionals from Fisher-Price, Optikos and Cambridge Design Partnership.

In addition to design work, these volunteers assisted in researching prior art, collecting customer feedback and other market data, and developing strategies for volume manufacture. Professional volunteers at DEKA research, Owl Engineering and Cambridge Design Partners, and design faculty at MIT and Worcester Polytechnic also assisted with regular design reviews at every stage of the prototype development process.

Designed by

Timothy Prestero & Neil Cantor managed this collaborative design process through Design that Matters, with the participation of 180 student and professional volunteers - United States