We all recognise and have even discussed at length, the importance of designing for death and absence. But how are we tangibly tackling the issues associated with mortality and loss? A new generation of designers are responding to the Death Positive Movement, which goes way beyond solving the technical problems in healthcare to creating meaning and guiding us through our final years. Here are six distinct examples of how designers are applying “grace, foresight, sensitivity and imagination” to end-of-life care to help us die more humanely.

How do we spend our last days in the best way possible?

A 100 years ago people died much earlier and mostly in their beds at home surrounded by family. But, in the 20th century, a lot of things happened. We developed new medicine like penicillin and built new big medical machines like the x-ray generator. As these machines were so big and expensive, we then created big centralised buildings to keep them in, which, today, are known as our modern hospitals. In Denmark alone, 75% of the population die in hospitals. But, only 5% and 1% of the population want to die in hospitals or retirement homes, respectively. Where we die is a crucial part of how we want to die. So, how do we improve these places and, therefore, our last moments alive?

Architecture could be a good place to start. Recently, I visited the old Hospital de Sant Pau in Barcelona, which is designed as a ‘park hospital’. The hospital was the first to acknowledge that physical surroundings can improve health. Therefore, they created a calm atmosphere using beautiful aesthetics, light, clean air and open areas to nature. Today, a lot of our hospitals are very compressed, impersonal and practical, even though studies show that people recover faster when surrounded by nature. Maybe we should draw more inspiration from the older days in order to improve our hospitals? A contemporary example is this building (above) currently in construction for the existing Herlev Hospital in Denmark. Here, the architects have tried to implement nature in the surroundings with, for example, open courtyards. In addition, they’ve designed a multi-religious centre to embrace the different needs and religious affiliations the patients may have. And around the hospital, a nature reserve is also being created to provide access to outdoor experiences, biodiversity and rainwater. It’s expected to be completed within the next year.

How do we cope with loss?

Designer Lisa Merk from Lund University has designed a series of small urns that people can hold during funerals to reduce anxiety. The wooden forms, which look like smooth wooden stones, contain a small amount of ashes from the deceased and are designed to fit comfortably in the hand of the user. “Since funerals are very emotional and stressful events, I wanted to provide something for the mourners that they could hold onto or even share their sadness with, at least for the moment of the service,” Merk explains.

What to do with our bodies?

In a time where atheism and non-affiliation with religion are rising, dying and potentially not ending up in ‘paradise’ is a scary thought for many. This biodegradable urn, known as the Bios Incube, transforms ashes into a tree and, therefore, continues life in a way. For many, becoming a tree is a comforting thought, whether you’re religious or not. Giving the body back to nature and, at the same time, creating a living object is a beautiful way to ‘continue’ into the afterlife. In addition, having a physical object to care for also gives comfort to families and friends, while even contributing to a healthier planet.

How do we cope with fear?

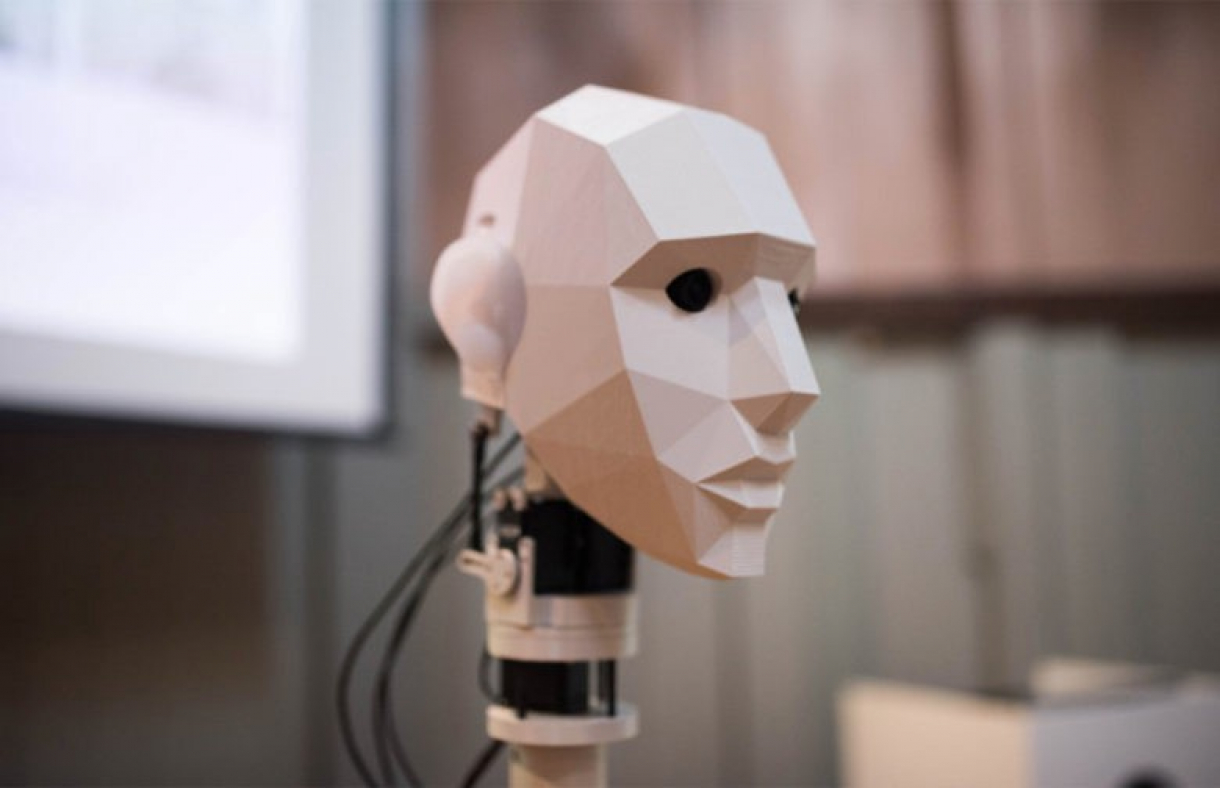

In healthcare, the majority of efforts and research focus on keeping people alive. But, fear and how to mentally prepare for death is often a neglected topic. However recent (para) psychological research suggests that the sensation of drifting outside of one’s own body using virtual reality could help reduce death anxiety. Outrospectre explores these findings in hospital surroundings where it could help terminal patients accept their own mortality with more comfort. This “out-of-body experience” is said to provide therapy for the dying by gently acclimatising them to the sensation of death. With Outrospectre, the creator Frank Kolkman intended to start a conversation about how designers can introduce a new culture of acceptance and openness about death in hospitals. “If we began treating our anxieties surrounding death, it might mean the process of dying could become more comfortable,” he explains. “Doctors are trained to save and prolong lives, not tend to our demise. “They simply lack the tools.”

How do we say goodbye?

This year, Funeral Home is nominated for INDEX: Award 2019. It’s a contemporary ceremony building to give the deceased a beautiful goodbye while celebrating their life. The building contains three rooms. In the first room called Wall of Memories, a floor to ceiling video wall shows videos and pictures of the deceased, which are provided by friends and family. After the ceremony, the collective remembrance can then be downloaded and taken home as a memory. After passing through the Wall of Memories, attendees move into a triangular space, which the architects HofmanDujardin say “creates intimacy in both small and bigger groups [thanks to] the two curved walls and ceiling, which bend inwards to define a passage as the centre for the coffin”. The also room has a big panoramic window that opens up to a garden, bringing the natural surroundings in. “The shape implies a flow back towards nature, closing the circle of life,” explain the architects. The third room is an event space, clad with timber, to facilitate the celebration of the life of the person who passed away. This modern and “religion-neutral” way of conducting a ceremony also creates space for the growing digital footprint we leave behind.