For me, 2020 is the year I established a tangible grasp on historical events. Born in 1992, this year brought me closer to understanding the consequences of fatal diseases spreading across continents and what the African American community's fight for rights actually looks like.

Past events are commemorated all over the world at public memorials, museums and historical plaques. People travel to Auschwitz-Birkenau to get a sense of the horrors of the Holocaust and visit the Killing Fields in Cambodia, where a million people lost their lives. The Plague Column in Vienna, Austria was erected in gratitude over the end of the plague epidemic in 1679 and in Golden Gate Park lies the National AIDS Memorial Grove in remembrance of lives lost.

It's not unlikely the events of 2020 will be remembered similarly. COVID-19 has killed almost half a million people and made a severe impact on world citizens who've been asked to stay inside, similar to what people in occupied nations were doing during World War II. Black Lives Matter protesters in the US are being attacked, reminiscent of protestors in Selma, Alabama in 1965, known as 'Bloody Sunday'.

I've thought a lot about how the current events bring me closer to understanding history. I'm a big museum-goer and always try to find the most impactful museums and memorials when travelling. But, of course, reading signs, seeing photos and walking through cement monuments have limits when it comes to making past events come to life. It's worth thinking about how we can design museums and memorials with more ingenuity.

I'll start the conversation with some ideas based on my visits around the world. Recently, I went to the US, which has heavily influenced these thoughts.

1. Designing for reflections, not photos

We've all seen how the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin, Germany has become an Instagram photo opportunity. This has been the source of many arguments when people upload happy-go-lucky snapshots or posing pictures at places of remembrance. Taking pictures at memorials should, in my opinion, not be prohibited and, there will always be those unbothered by what other people think. But, how can we communicate the gravity of a past event to the place where a memorial stands?

In Hiroshima, Japan, The Atomic Bomb Dome stands as the only original building left near the atomic bomb's hypocenter. Its sheer presence is a powerful gateway to that day in August 1945, and truly communicates the weight of the event to visitors today. Not all memorials will be able to build their foundation on the actual elements of world history, but, they're a vital force in expressing untouchable and undisputed realities.

2. Making journeys instead of standstills

Journey design makes such a difference when you're trying to make something intangible feel very real and relatable. All over the world, memorials are made from small and tall statues, massive columns or an eternal flame. We can stand and look, but how do we immerse ourselves into the stories behind the material? Perhaps by physically walking through it?

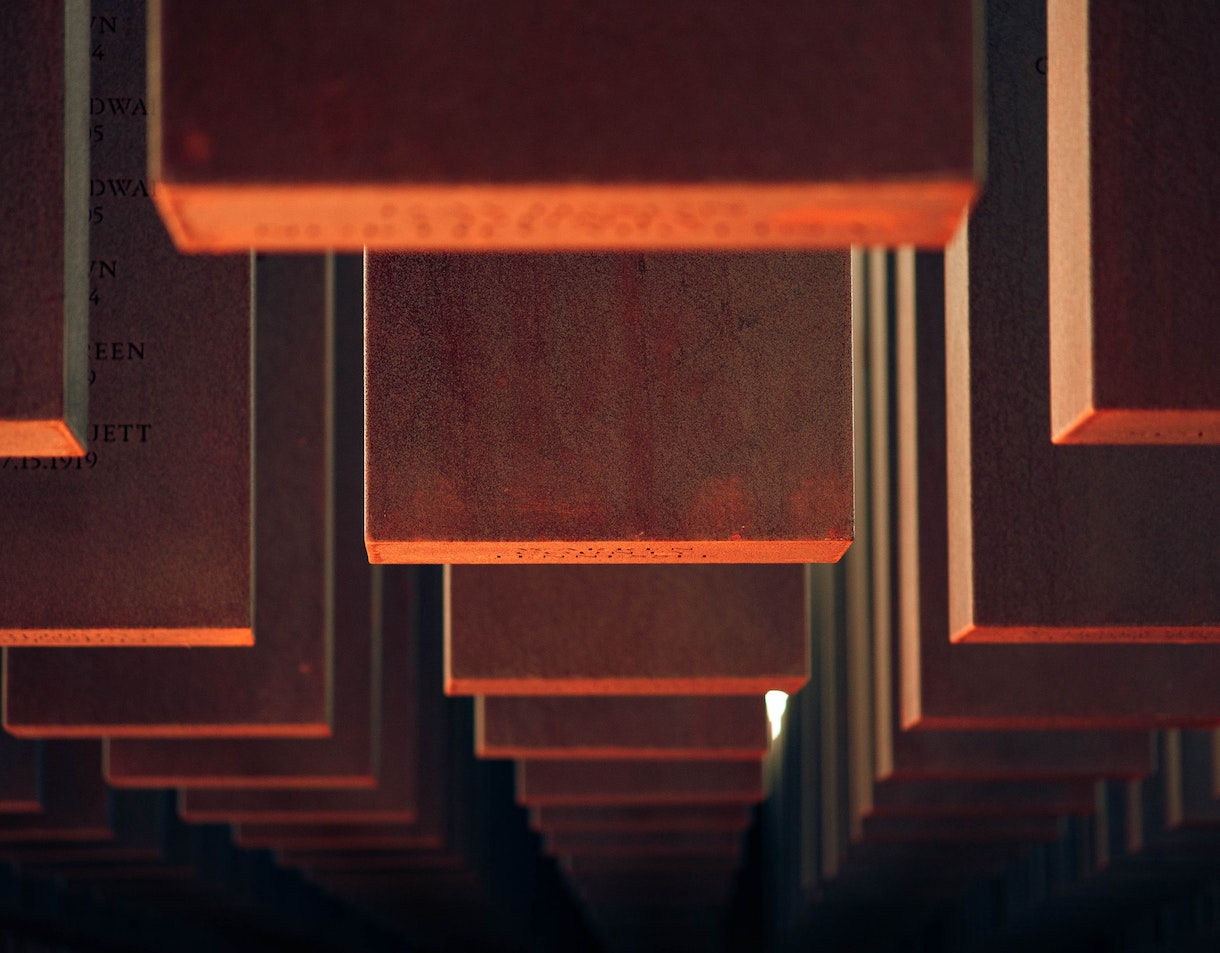

In Montgomery, Alabama, lies The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which is dedicated to remembering the victims of enslavement, lynching, segregation laws and police violence. The experience is very immersive as you enter the memorial by walking up a hill providing detailed information on the past —and very much current— history of lynching in America. In the memorial, you walk under concrete blocks filled with victims' names and pass beautiful quotes, like this one that has personally stuck with me.

3. Connecting to the present

Memorials are about remembering the past but also help us understand society today. They're not just about making connections but help us move forward with an enlightened perspective to change the status quo. The National Memorial for Peace and Justice and the Legacy Museum are spaces I've been to that question the present and encourage change in a proactive way. The exhibition hall, where enslaved people were once warehoused, features letters from currently incarcerated people and chronicles how past injustices have shaped today. Visiting a museum based on the present somehow made it easier to understand how issues like this could easily happen a century ago.

So, how will we remember the events of 2020? It's clear that we must go beyond textbooks and marble statues. I'd love to hear what memorials or museums have impacted you the most, please feel free to send me your thoughts.

-

Images: Ferdinand Stor, Mitchell Griest, Tomoaki INABA, & Koshu-Kunii.