Many can remember when they first learned that life has an end. For me, it was in the second grade, when the fish in the tank in my classroom grew a bulge. Although there was only one fish in the tank, in our seven-year-old minds, the fish was pregnant with white, black, and gold baby fish, and maybe we could each take one home. One morning, the tank was gone. Our substitute teacher informed us the fish was floating upside down, so she drained the tank into the toilet.

In becoming an adult, I've learned it takes two fish to make baby fish, and one day I'll be the proverbial upside-down fish flushed down the toilet. Everyone is aware that there is birth, and there is death. And as my team began researching the end-of-life, we oriented ourselves to the assumption that death is scary and that everyone fears the end. However, after researching for this project, I've slightly reoriented my thinking. Perhaps it's not the end of life that's terrifying; it's the thought of all that can't be known while life is going on around you, the feeling of swimming aimlessly, beholden to a world outside of control.

In January of this year, The Index Project sponsored a semester-long research project for graduate students at The Carnegie Mellon School of Design. My teammates and I chose to focus our intervention around the topic of end-of-life.

”Perhaps it’s not the end of life that’s terrifying, it’s the thought of all that can’t be known while life is going on around you."

We focused on end-of-life legal documentation, wills, power of attorney, medical directives, etc. during the research phase of our project. We responded with astonishment when people in their 50s and 60s remarked they had no legal plans for end-of-life. Then after a few weeks of research, we toured an elder care community. This beautiful facility features floor to ceiling windows, communal kitchens with marble-topped islands, and a restaurant for use when families visit. Before we left, some of us sat in the car, sharing a sinking sense of dread.

The majority of residents had financed their stay through pensions and the sale of real estate. Pensions are virtually nonexistent for my generation, and few of us have illusions of owning homes. Suddenly death seemed much more straightforward than planning for retirement.

A few weeks after that, COVID-19 upended our daily lives and changed our perceptions of what was ahead. In our endless Zoom meetings, we reoriented scope to focus on how planning could be utilised to create peace of mind during unprecedented times. We presented our final concept in May — Life, an app designed to teach people that planning for death would help them feel more in control of their futures.

We were aware emergencies can't be the only catalysts to bring agency into our lives. The differentiator between Life and other virtual legal services is that we considered the lived experience along with the documents and perfunctory end of life tasks necessary in an emergency.

We envision incorporating acts of planning as swings of momentum beside memorable events, allowing our users to remember what they want to protect as they move forward. The timeline acts as this mechanism, visually representing the scope of what we've experienced, so we can imagine the years that lie ahead as reflections of the people and places who've made us who we are. In this way, although looking into the future I can't predict where I'll be and what events might unfold around me, I can remember the good things that led up to now, and anticipate there will be more to come.

"The concept of future planning is fruitless if you can't picture a future you’d want."

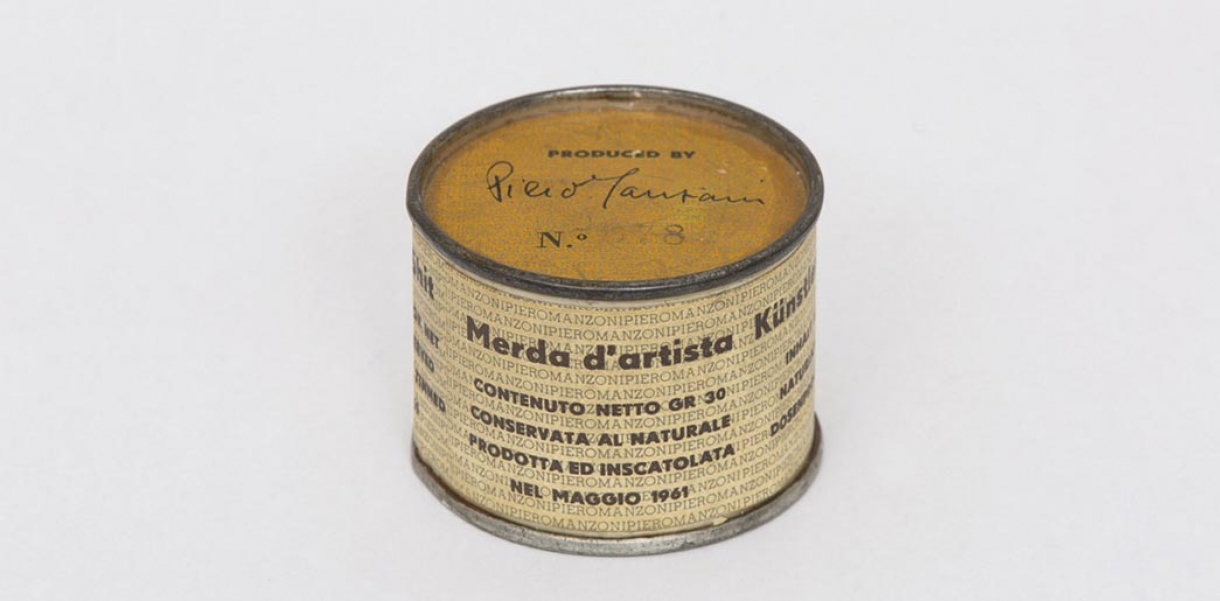

Less than a month after our submission, the street outside my apartment that had been eerily quiet in March, was raucous chanting and marching as crowds broke out across the United States to protest our country's legacy of institutionalised racism. These outcries for equality have given much optimism. Still, they exist alongside a pandemic that is growing and a sense of dread among many that the virus and the protests may culminate in a tumultuous election in November. It feels like we stepped on a precipice in 2020, and in a year that's only halfway through, guessing what will happen long term feels like a hollow and futile gesture.

In 2010 when I imagined myself ten years in the future, I envisioned someone with more stability, income, clarity, a woman whose decade of experience would make her better suited to make decisions. Now looking ten years into the future, I've no idea, two years into the future, not a clue. I now imagine feeling prepared for an unexpected emergency would be calming.

Still, an app can't provide the peace of mind that society will become more equitable or assurances in life will continue as expected. The only peace of mind we may get might come from looking back at the times that went well—remembering the people and places where we felt safe and imagining replicating those moments in the future. After all, the concept of future planning is fruitless if you can't picture a future you'd want.