A few years ago, I travelled to Finland for the Arctic Design Week, hosted in a little town in Lapland well-known to be the city of Santa Claus. The day after the conference I had time for a walk around the city centre, and one of the things stuck in my memory is the public library designed by Alvar Aalto.

The library is in a beautiful location, and when I entered the building, I had the feeling of entering a sacred place — appreciated and loved by the local community.

The warm light, curved walls, smooth surfaces, and the natural materials of wood and glass gave me a peaceful feeling. It's architecture that welcomes and embraces the people working or visiting the library.

I first heard about Alvar Aalto from my art teacher in high school — she told us that she had forced her travel companions to drive hours in the middle of the Finnish forest to go and see this particular hospital Aalto designed.

After studying product design and, later on, moving to Northern Europe, for me, Aalto became more of a great design master to look to for inspiration.

But, why and how can a hospital facility can be so impressive?

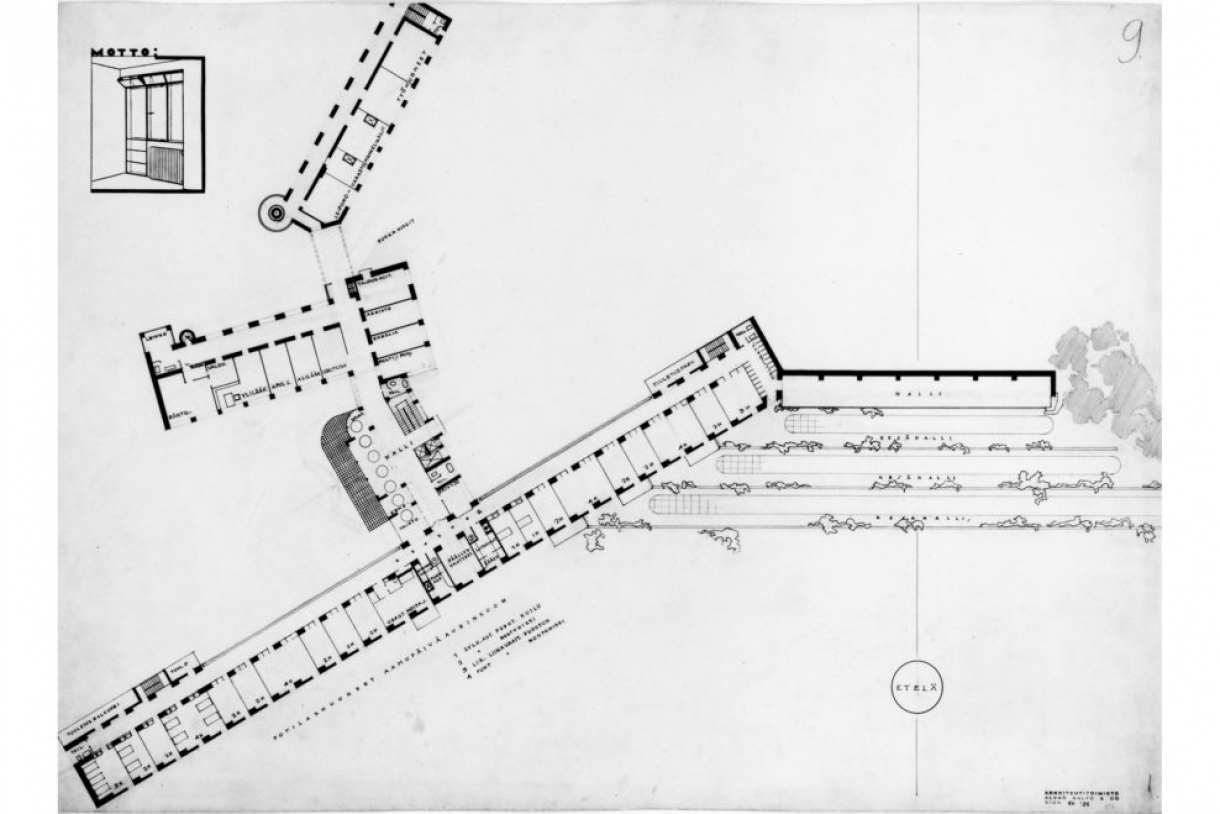

Paimio Sanatorium was designed at the beginning of the 1930s when the human-centred design approach was still far away from being a buzzword in the architecture and design sector.

"The building was, quite literally, designed from the users' point of view."

Nevertheless, Alvar Aalto used this project to experiment with several theories on ergonomics and comfortable environments, of architecture or design, for the end-user and their needs.

The central purpose of the Sanatorium was to create a space to promote the healing and rehabilitation of tuberculosis patients. As there were no medical treatments for tuberculosis at the time, the most efficient treatment was isolation to prevent the spreading of the germs combined with exposure to sunlight and fresh air.

On the top floor, he designed a roof terrace facing south where the patients' beds could be moved to throughout the day. The windows facing toward the surrounding landscape were positioned lower than usual, allowing patients laying in their beds to be able to feel the sunlight on their skin and appreciate the beautiful natural panorama. The building was, quite literally, designed from the users' point of view.

This level of attention to detail provides a clear perspective on how much the designer thought and cared about the people living in the building and their needs.

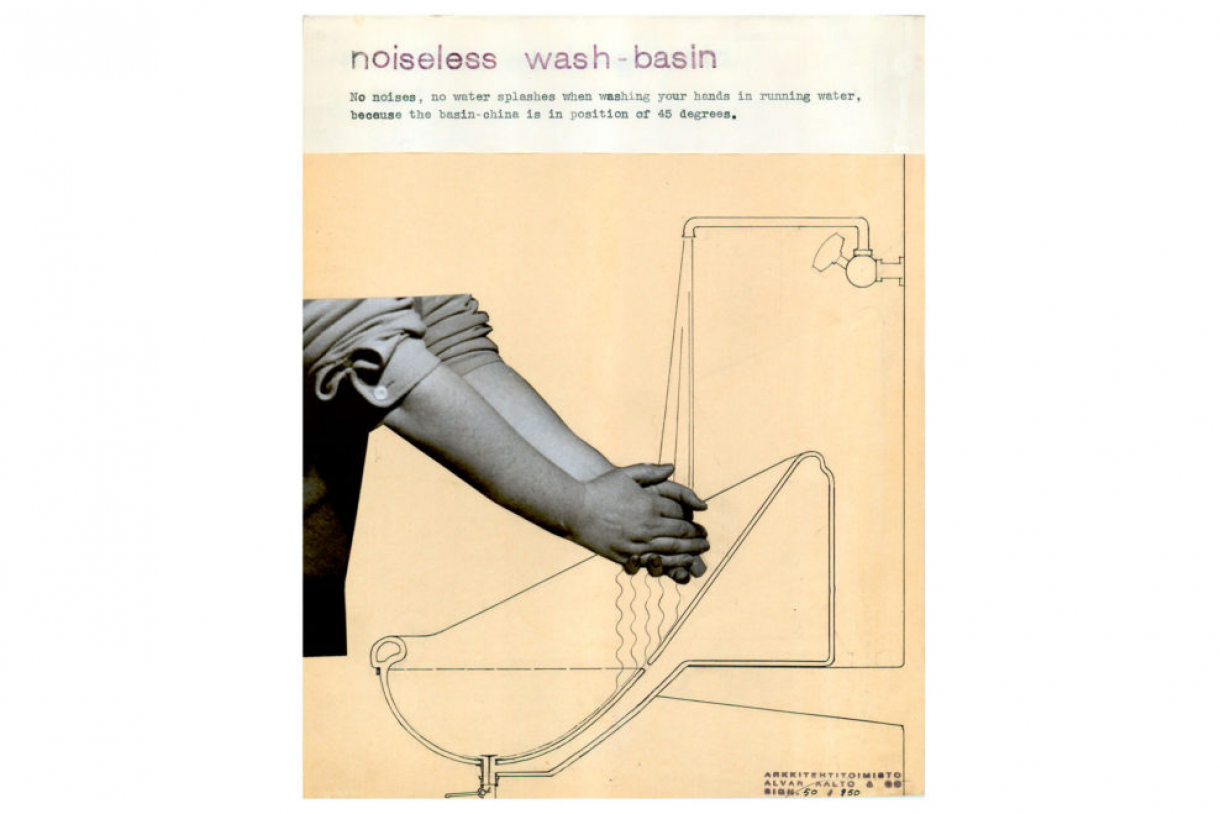

Another example is the design of each hospital room, which had to accommodate two people. The rooms' sinks were meticulously shaped to dampen the noises of running water or dripping, which could disturb others if patients washed their hands during the night or resting time.

The door handles of the rooms along the Sanatorium's long corridors were curved inwards into special rails, to prevent the handles catching the coat sleeves of doctors and medical staff.

"Aalto strongly believed in chromotherapy and felt that colours could play a "medical role" in the healing process."

The handrails on the stairs were designed to become smaller as the stairs ascend; this was to both help doctors rapidly climbing between floors and support patients going down.

Alvar Aalto also designed the light fixtures and furniture of the Sanatorium together with his wife, Aino Aalto.

A considerable amount of research and attention was given to the colours and type of light. Aalto strongly believed in chromotherapy and felt that colours could play a "medical role" in the healing process. As patients spent most of their days lying down, Aalto placed the lamps in the room out of the patients' line of vision and painted the ceilings in a calm dark green.

One of the most iconic articles of furniture used in the hospital is the Paimio armchair, which has been repurposed in countless variants from multiple brands, including IKEA. The shape of the chair's back aids breathing and has been designed with no sharp angles or any fabric to be as hygienic as possible, avoiding the spreading of bacteria from one patient to the other.

Nowadays, the Sanatorium is no longer in use, but it still inspires people all around the world. It shares the straightforward message that a good designer must first be a good person. Or, perhaps it's as Aalto puts it: "We shape our buildings thereafter; they shape us."

-

Images: Alvar Aalto Museum